In defence of the testing pyramid

I like simplified models to guide decisions on how to build systems. There’s enough complexity in any software project, that without some guiding principles that at least seem theoretically correct, we’re likely to make suboptimal choices based on a coin toss. Simplified models neatly encapsulate the experience from previous attempts at doing something and help inform the future attempts.

So long as they are not too simplified. To actually work, the models need to be clear, reasonably complete, and actionable. If I have a concrete question, even as simple as a decision between two alternative approaches, the model needs to give me clear guidance on how to proceed. Case in point, the testing pyramid:

Image source: https://betterprogramming.pub/the-test-pyramid-80d77535573

Image source: https://betterprogramming.pub/the-test-pyramid-80d77535573

We’ve all seen this picture. It is a seemingly helpful guide: To minimise cost of testing and maximise reliability and resulting quality, put more effort into, and rely more on tests closer to the implementation than the tests that are covering a wider scope. Seems intuitively correct, but fails my criteria: It’s unclear what integration tests and even unit tests actually are, specifically. It also doesn’t help answer questions like “Should I run end to end tests on every pull request?”. And where does static analysis fit in? – it’s unclear, incomplete, and it isn’t actionable.

As a consequence, people don’t seem to find it particularly helpful, and even propose various modifications which resonate with their experience better, like the testing trophy, proposed by Kent C. Dodds. I think these variants come down to the misalignment about what the individual layers of the pyramid are, what value they bring, and how costly they are to execute. And I’ve seen one too many testing strategies in which the pyramid is completely upside down, but the engineering team just doesn’t know how to do their testing any better. The pyramid is supposed to guide them, alas it stays quiet.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the pyramid. It’s just not quite detailed enough to be useful. Good first approximation, but I think we can do better.

Some Assumptions

To make a better version of the pyramid, I will need to make some assumptions about the kind of system we’re testing, and the high-level ways of working of the team, and roles involved in the building of the product. At a high level, I will assume that:

- We’re building a distributed system, composed of independently deployed services and applications. Running the entire system requires an environment.

- Our system has external dependencies which we don’t control - services delivered by separate organisations or other, independent teams in our organisation

- We’re doing continuous delivery, even continuous deployment to production, and therefore heavily rely on a Continuous Integration (CI) service

- Our branching workflow resembles Github flow - we have a single main branch, into which contributions are made in the form of small pull requests which get reviewed before merging

This feels like a pretty typical situation most digital product teams find themselves in. The situation is probably different for game developers, desktop software developers, machine learning engineers and data scientists, and others. So, as always, your mileage may vary.

The improved pyramid

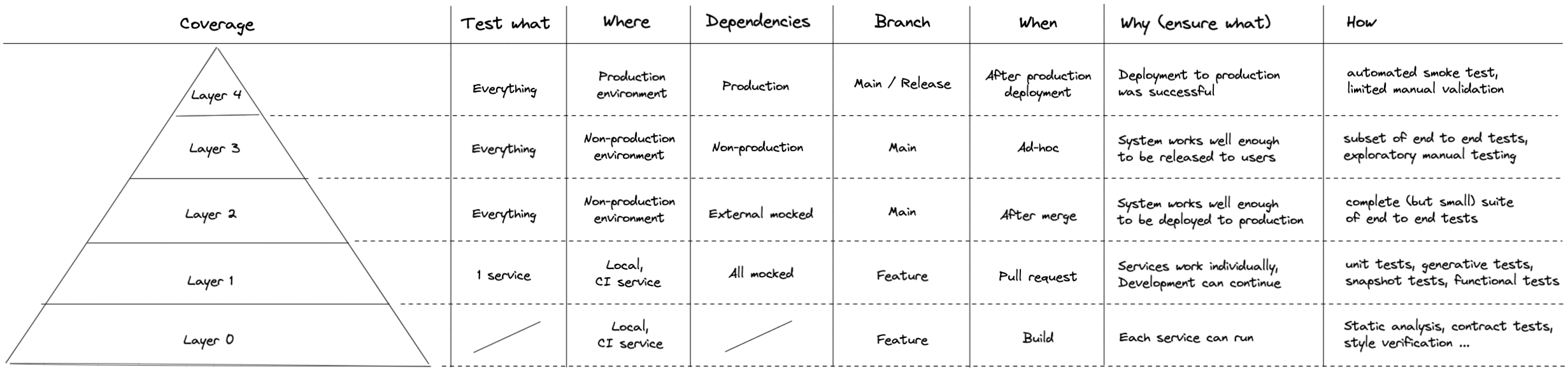

With that out of the way, here’s a (hopefully) more complete and useful pyramid:

This one has five layers, which are defined by what gets tested, where, when, why and how. The layers still form a pyramid, because in order for the upper layers of the pyramid to pass (or even run), the lower layers have to have passed first. Upper layer tests require more setup and more infrastructure, which makes them much more expensive to run than lower layer ones, so the overall volume of testing on the upper layers needs to be lower to maintain a stable cost/benefit ratio across layers. Or, from a more outcome oriented perspective:

The goal of each layer is to more cheaply and more regularly gain a reasonably high confidence that the layer above will pass, so that it does not need to be run as often

In other words, the lower layers are an optimisation of executing the upper layers, in order to reduce their cost while maintaining a high enough overall confidence in the system.

Changing tests with implementation is fine, top-heavy pyramids are not fine

Some will argue that pushing tests lower, closer to the implementation will lead to us having to regularly change tests when we change implementation, and that the execution time saved will instead be spent on keeping the lower layer tests up to date. To that, I will say that the idea that it should be possible to change implementation without changing tests is just… nonsense.

If it were true, it would mean that everything can be exhaustively tested through the interfaces it is consumed through - through the UI or public API, or something very close to it. That thinking obviously completely ignores the “physics” of software, and all the reasons we are building systems in a decomposed, modular way, which encapsulates and reuses logic. The sheer number of test cases necessary to capture all the nuances of all our business logic all at once is just not practical. And it’s not difficult to show that.

Let’s say each logical “unit” of our software requires, on average, 10 scenarios to test it thoroughly. Then, if these units are in any way dependent on one another (either one uses the other, or it uses the resulting state the other created), the number of scenarios multiply, and there are a 100 scenarios to cover for just two units, a 1000 for three, … This clearly doesn’t scale even a little bit! Let alone if our system is a complex sequential user journey, like an onboarding flow or a checkout in an online shop. That’s why we decompose software into functions and modules in the first place.

No other discipline building even remotely complicated things approaches testing in that way. Nobody sane would argue that a car should be tested only through driving it, on an actual public road, because otherwise we’d need to change the tooling when we change components. Of course the engine is tested independently from the tyres and the chassis. Therefore, the only remaining question is - how big is a unit we will test. And the bigger it is, the more tests are needed to cover it. And the more tests will need to be written again, if the unit is changed substantially. This is an inevitable reality driven purely by the complexity of the system, and doesn’t mean we shouldn’t build instrumentation for its constituent parts, just because we might replace them.

External dependencies are costly

You might also argue that layers 2 and 3 seem like an artificial split. We should be able to test everything on layer 3, surely. And in an ideal world, we could. The problem with testing against non-production environments of external dependencies is purely practical:

- They are not always available

- They are often slow or rate limited

- They lack test data or require creating it for every run

- They are stateful

All these reasons make repeatable, reliable testing solely against external systems difficult. But fully relying on mocks is not a reliable strategy either. We need to be sure that the mocks still behave like the actual system. We need to do both.

Guiding principles

So, we now have a more complete version of the pyramid. To make it an actionable model, we just need some overall guiding principles:

- All layers of the pyramid are necessary in order to achieve a high confidence in your system.

- Always prefer testing functionality on lowest possible layer.

- When a layer of testing starts slowing you down, reduce the volume of that layer and replace it by coverage on the lower layers. Introduce new forms of testing on lower layers.

- Do not give in to the temptation of moving layers “left” in the development process, executing the more expensive ones earlier or more often.

The last principle is worth talking about a little more. It suggests, for example, that running automated, system level, end to end test on each pull requests, as tempting as it sounds, is not worth the effort and complexity. End to end tests require an environment to run in (see assumptions), which would need to be created and destroyed (or allocated and cleaned up) for each pull request. In my experience, this is really complex, slow and highly unlikely to pay off in additional confidence gained, compared to running the end to end test(s) on the main branch, after merging the pull request.

With these principles, I hope the model is now actually useful - clear, complete and actionable. It should be possible to take every form of testing you can think of, decide what layer it belongs to, and therefore where and when it should execute.

Building up this pyramid will take time, and at first, expanding the higher layers will pay off much more than the lower layers. But these are diminishing returns. That’s why so many teams come up with an upside down pyramid that takes hours to run and still lets many bugs through. It’s so tempting to just add another end to end test. Don’t fall into that trap. Follow the above principles, and turn the pyramid the right way up.

Built to be testable

I have one final observation about all this: If, despite your best effort, you can’t seem to push test coverage down the pyramid, you may need to revisit your architecture, or even technology choices. Testability entirely depends of how your system is built.

In a system without stubs of external dependencies, achieving reasonably high coverage with automated end to end tests will be difficult and slow. In a system with services sharing state (a database for example), pushing tests from layer 2 down to layer 1 will be difficult. In a codebase with no concept of dependency injection (even a really simple one), moving coverage from functional tests to unit tests will be difficult (and require extensive, messy mocking and stubbing). In a system without contract testing or shared API types ensuring client/server alignment on layer 0, a lot more layer 3 tests will be required to gain the same level of confidence. In a dynamic language with few static guarantees, layer 1 will almost certainly be much larger than layer 0.

I could keep going, but you see the point. Fast reliable testing begins with smart engineering. Hopefully this more specific pyramid will help you make smarter choices.