Microfrontends

Introduction

As we build larger and larger single page apps, it becomes increasingly difficult to maintain the codebase, particularly if multiple teams are working on it.

On the backend, there are increasingly established patterns for decomposing large monolithic services into microservices, but less has been said about solving the similar problem for frontend monoliths. However, the idea of microfrontends is starting to gain some traction.

Microfrontends is an approach for decomposing a monolithic frontend application into smaller components, which come together to form the whole app. I’ve recently been experimenting with this approach, and this post describes some things I learned along the way.

An example

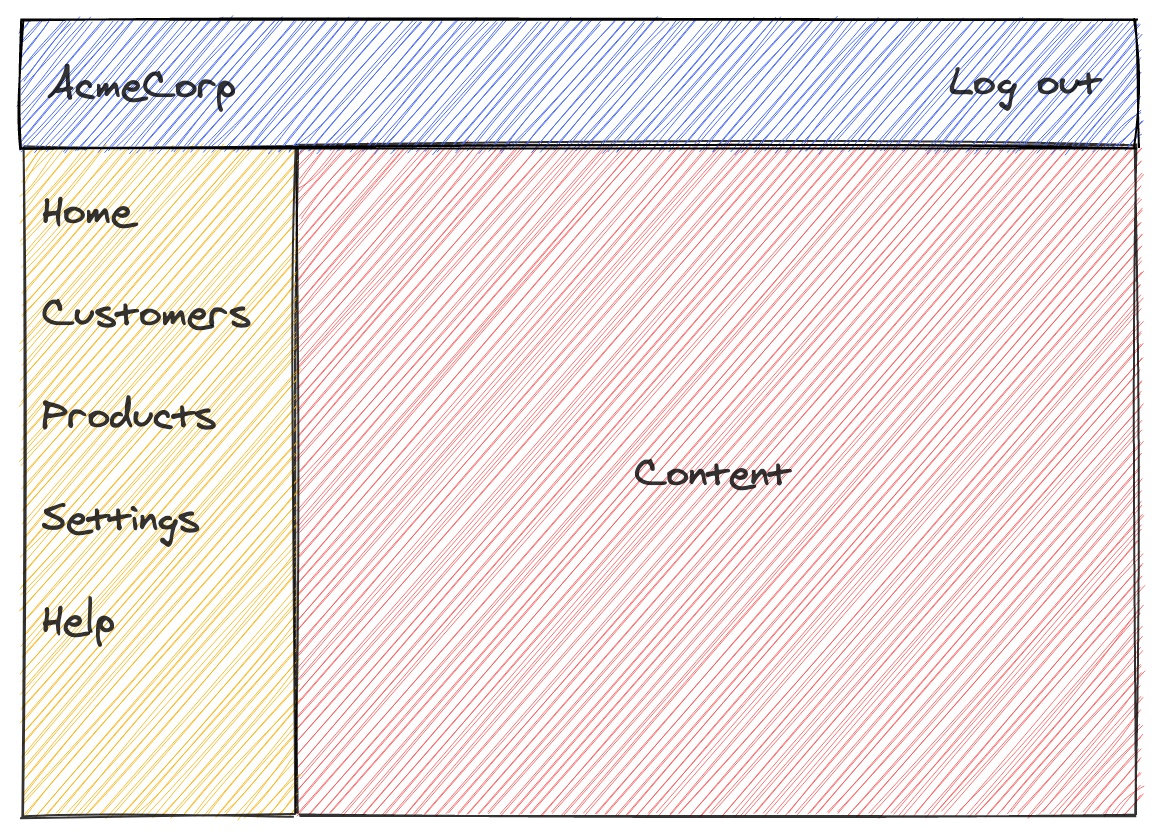

Let’s imagine a dashboard for users of a SaaS product. Each page of the dashboard has a header on the top (blue), a navigation bar on the left (yellow), and a main content area (red).

To start with, the dashboard is deployed as a single monolithic single page app. As the product grows, more and more pages are added to the dashboard, and they become more and more complex. Different teams start to own different pages, but are still working within the same monolith. This means that it gets increasingly difficult for the teams to ship independently, as their code is tightly coupled with that of other teams. Upgrading libraries and maintaining green builds are tasks that need co-ordination between teams, as they all have dependencies on each other.

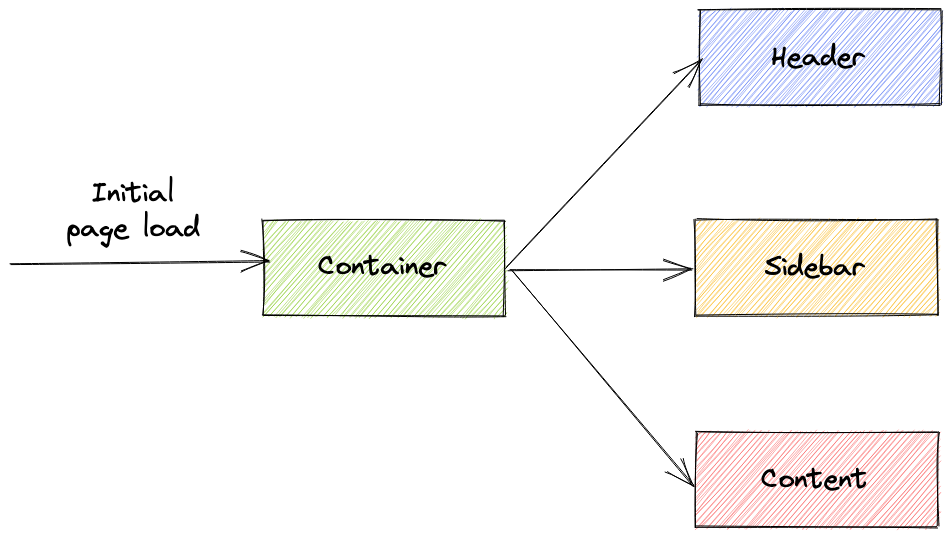

In the microfrontend approach, we would deploy separate services for the header, sidebar, and each content page that we want to display. Another container service is the entrypoint for the dashboard, and is responsible for fetching the relevant services and assembling them into the whole page. Each service just needs to serve a JavaScript bundle for creating its part of the page.

This is analagous to a microservice architecture, where an incoming API request might trigger requests to several downstream services, that get aggregated together into a combined response. The benefits are that each of the services is smaller and simpler, and can be deployed and operated independently of all of the other services. It also means that different services can make different technology choices (for example, using different frameworks).

Deploying a microfrontend

We use web components to include a microfrontend inside another app. This allows us to define our own custom HTML elements and embed them in a page.

We make use of the shadow DOM within our components so that they’re isolated within the page. This effectively creates them within a separate DOM that the containing DOM can’t see, so the component can set its own styles.

The component itself can be implemented with any framework, with a small wrapper to turn it into a web component. Here’s an example of wrapping a React component within a web component:

import ReactDOM from "react-dom";

import styles from "./styles.css";

// Our microfrontend, implemented in React.

const SayHello = ({ name }) => <div>Hello, {name}!</div>;

class SayHelloElement extends HTMLElement {

connectedCallback() {

// Create a shadow DOM.

const renderRoot = this.attachShadow({ mode: "open" });

// Create a div for our React app to render into.

const container = document.createElement("div");

renderRoot.appendChild(container);

// Add our styles to the shadow DOM.

const styleTag = document.createElement("style");

styleTag.innerHTML = styles;

renderRoot.appendChild(styleTag);

// Render our React app into the div.

const name = this.getAttribute("name");

ReactDOM.render(<SayHello name={name} />, container);

}

}

// Make our custom HTML element available. The name must include a dash.

// It can be used from elsewhere as:

//

// <say-hello name="Alice"></say-hello>

customElements.define("say-hello", SayHelloElement);

The key idea is that this wrapper allows us to encapsulate a component from another service entirely within an HTML tag, regardless of the underlying framework or technology. This is supported in most browsers, but you’ll need to include a polyfill if you need to support IE11.

Communicating between microfrontends

As with components in other frameworks, microfrontends need to be able to share state and update each other based on events.

As seen in the example above, one way this can happen is by passing attributes into the custom HTML element, in a similar way to passing props into React components.

Components also need to communicate with their parents. Again, following the example of React apps, one approach to this would be to pass a callback function into the child. However, this can introduce coupling between different parts of our application, which could be otherwise unconnected, and we want to avoid that.

Going back to the analogy with microservices, we often solve this problem by having an event bus. Services can publish events to the bus, and then other services can consume them to process them.

We can take a similar approach with microfrontends using custom DOM events. A microfrontend can emit events which other microfrontends can listen to and process (for example, by adding an event listener that updates a piece of state in a React component).

Managing the event bus

One downside of the event bus approach is that it becomes harder to determine and enforce the contract between microfrontends. This is a problem that’s shared with microservices.

One approach to managing this complexity is to use explicit schemas for each message sent on the bus, e.g. using JSON Schema. The schema is defined by the microfrontend that emits the event, and all events are validated against that schema before being published. The microfrontend makes the schema available at a URL which is included as part of an envelope that wraps each message.

A developer might want to see documentation for all of the events, so that they can understand what they mean and how to implement the feature. If the schemas are hosted at a known endpoint in each microfrontend, it’s possible to build tooling that can find and aggregate all of the schemas together and build a documentation site.

It might make sense to have a shared library for emitting and subscribing to events, along these lines:

import { validate } from "jsonschema";

const EVENT_NAME = "event-bus";

export const emit = (schema, event) => {

if (!schema.title) {

throw "Schema must have a title";

}

validate(event, schema, { throwAll: true });

const detail = {

topic: schema.title,

schemaURL: `http://${BASE_URL}/schemas/${schema.title}`,

payload: event,

};

document.dispatchEvent(new CustomEvent(EVENT_NAME, { detail }));

};

export const subscribe = (topic, handler) => {

document.addEventListener(EVENT_NAME, (event) => {

if (event.detail.topic === topic) {

handler(event.detail.payload);

}

});

};

In this example, all of the events are published with the same name. This means that a developer can inspect the full event bus by adding a single event listener in the browser’s JS console:

document.addEventListener("event-bus", (event) => console.log(event.detail));

For apps with very many events, there may be some performance issues with putting everything on the same event name. In that scenario, you could instead have different event names per service or event topic.

Sharing library dependencies

One of the major drawbacks of the microfrontend approach is that, if we generate a single bundle for each microfrontend, then we may end up significantly increasing the amount of code that a user has to download to view the page. For example, if every microfrontend uses React as its main framework, then the user would have to download one copy of React for each microfrontend that appears on the page, which can add up to a significant size.

There are a few options for alleviating this pain. The simplest approach might be to load a single global copy of commonly used libraries; however, doing this means that all microfrontends will depend on the same version of those libraries, which makes upgrading them more challenging, as all of the microfrontends will need to be upgraded together.

A better option might be to use bundle splitting to separate large libraries into their own files, which can be loaded by multiple microfrontends and cached by the browser. If there are a small number of frameworks (and versions of those frameworks) in use across the microfrontends, then this could be a significant saving. Webpack’s module federation feature could be a good way to achieve this. Alternatively, the problem could be mitigated by using smaller frameworks, such as Svelte.

Conclusion

Microfrontends are an interesting approach to the challenges of building and maintaining large single page apps, borrowing ideas from backend microservices that have proved useful in similar situations. I’ll be keeping a close eye on this space and will have it in my toolbox the next time I’m building a complex frontend app.

Further reading

- Micro Frontends: article by Cam Jackson

- micro-frontends.org

- Micro Frontends in Action: book by Michael Geers