Platform (R)evolution

A look at how platforms for distributed systems are evolving — how they are rising up to meet ever lighter workloads — and charting a journey from Kubernetes, through Istio and Dapr, to wasmcloud and beyond.

Houston, we have a problem! We made distributed applications too hard! And now we need to be super-humans in order to build, run and manage them.

Docker containers were so much lighter than virtual machines that we used them everywhere to package up all the pieces of our new microservices applications. Then we invented Kubernetes to manage them for us. But we forgot how many concerns we have to manage in order to be secure, scalable, reliable, and resilient.

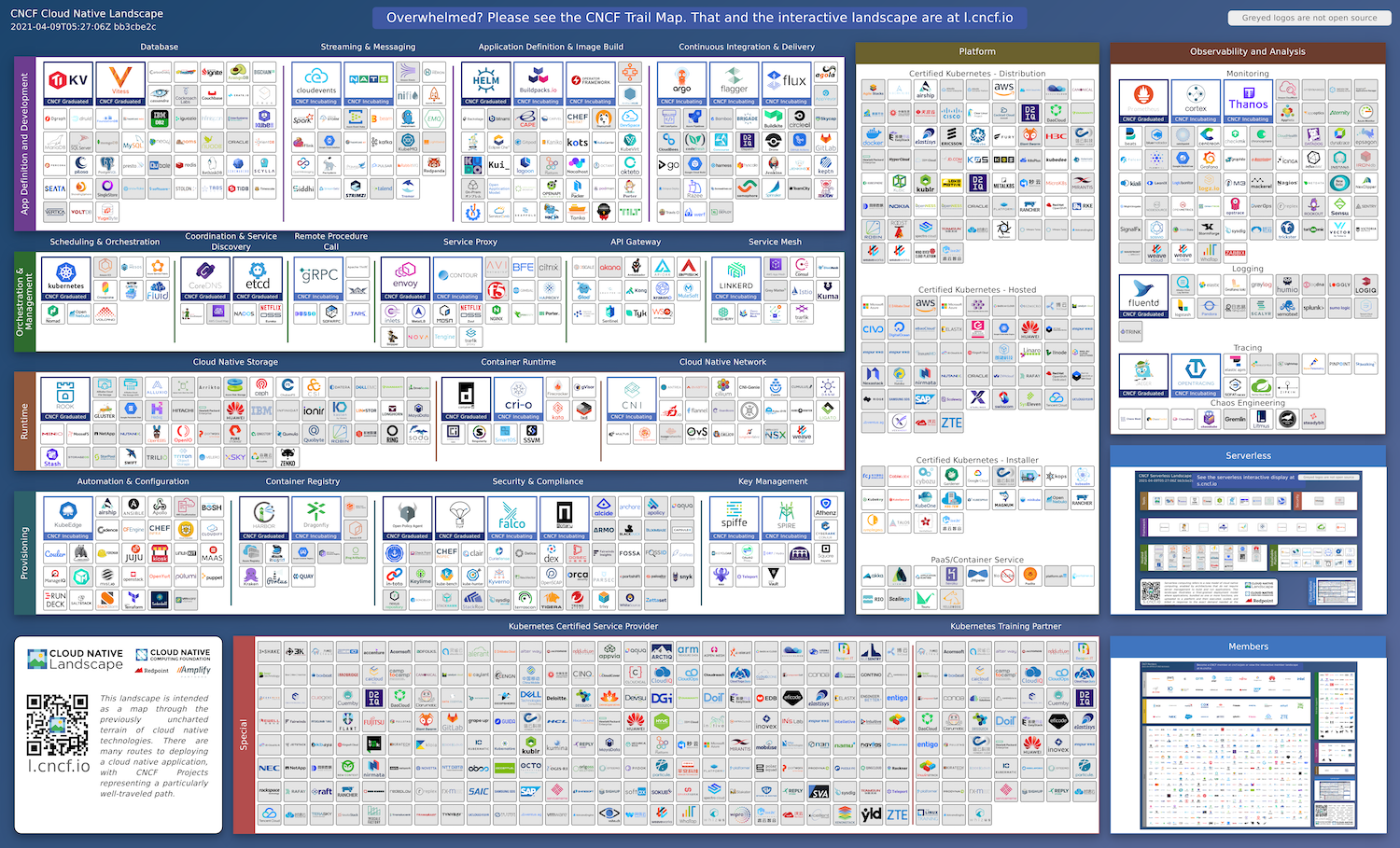

So we added a bunch of other tooling on top of Kubernetes to do that for us. And we made the CNCF Landscape, which currently has nearly a thousand products (with a market cap of $15T and funding of $16B). A whole new industry, which we expect DevOps-focused teams to navigate. The bar of the “T” (of our T-shaped engineers) is suddenly wider than the Suez Canal, and we’re in danger of getting seriously stuck.

When I look at a complex landscape like this, I wonder if all that complexity is actually just propping up the wrong solution.

We have really made a rod for our own back with microservices and DevOps. Whilst I agree with the philosophy of small, independently evolvable (and deployable) services that “do one thing and do it well” (as per the UNIX philosophy), the price we pay for this today is way too high.

This is probably due to the relative immaturity of microservices as an architectural pattern — there are a lot of problems to solve in distributed systems, and so far, it seems, we have lots of individual solutions.

Large enterprises address the problem by having separate platform teams. This is great, if you have the resources to do it, because it allows the separation of focus above the platform from focus below the platform. Over time, patterns that are established can be pushed down into the platform, making it easier for cross-functional teams to concentrate on user value.

But if you don’t have a platform team, what do you do?

It feels, to me, like we need to take a step back and look at the big picture again. I guess evolution will get us there in the end, but if we can already see something better we may benefit from a revolution instead.

Fortunately, software engineering is all about abstracting away complexity, so let’s do that. I think we can start by focusing on what’s important and shedding the rest through abstraction. I’ve written before about how the ratio of functional code (e.g. our core business logic) to non-functional code (e.g. talking to a database) in our microservices is way too low, and how the Onion architecture comes to our rescue. In that article I talked about how running much smaller, lighter workloads (the functional core of the onion) in server-side WebAssembly runtimes might eventually replace running larger workloads (functional and non-functional — the whole onion) in Kubernetes. Even with containers, each microservice carries around its own operating system, and networking is still a major concern.

Kubernetes is right at the centre of the CNCF landscape, it has become the de facto “operating system of the cloud”. It was intended as a platform for building platforms, and its extensibility has played a large part in its successful domination of that space. It’s certainly spawned an incredible amount of additional tooling. But maybe all this extensibility is a bit of a poison chalice, ultimately making it just too hard to use. Either way, the quantity of amazing innovation that it has seeded is simply mind boggling.

Now it feels like we can make the platform all together more intelligent, bringing it up to meet the core logic in our services, whilst allowing us to simultaneously reduce their weight. We can see this happening already.

Istio, and other service meshes like Linkerd, augment the platform at the network level. That’s a great start, which Dapr builds upon by augmenting the platform at the application level and acting more like an application framework (abstracting away IO, storage and other technical concerns). They both build on top of Kubernetes and even though, in my opinion, they give more than they take away, they do add to the cognitive load and complexity of the platform.

We are not removing the complexity, we are just moving it around — although we’re pushing it to the outer layers in the Onion architecture, so it’s a step in the right direction.

However, our microservices, whilst becoming more focused, are still subject to the underlying network topology, requiring us to understand, in detail, exactly how each part will communicate with the other parts of the system.

Wasmcloud takes a fresh approach, which addresses most of the issues that microservices currently face. For example, wasmcloud clusters are self-forming, self-healing, and unaware of network topology and protocols — they communicate over a secure NATS messaging infrastructure, which can be global (e.g. NGS). Furthermore the workloads (actors) run in WASM sandboxes, rather than OCI containers, making them extremely lightweight and focused (just the core of the onion). Importantly, they are restricted, in a cryptographically secure manner, to using only the specific capabilities they are given access to, both at design-time and at run-time. This is a truly zero-trust environment that is designed for running modern microservices — in the cloud, or at the edge — which frequently contain open source code that may contain vulnerabilities. Finally, wasmcloud is optimised for developer experience (DX), allowing engineers to deliver more customer value, much more quickly. We can see how the platform is rising up, even as our services are becoming lighter.

Unison, and the upcoming unisonCloud, in my opinion, take all this even further. Why run our code in containers or sandboxes at all? Why not just run it directly, on a substrate. Unison takes a unique and innovative approach to writing code — functions are immutable, content-addressed, units of code that are not text files, and only need compiling (and testing) once. Functions can be passed around with impunity to run anywhere that is suitable. They use algebraic effects, which they call “abilities”, to abstract away side effects and allow us to call capability providers from pure functions. We can see this as a logical extension of wasmcloud’s capability providers (and indeed dapr’s bindings), continuing to push the outer layers to the edge and down into the platform in a structured way. Unison as a language is coming on nicely, but it’ll probably be a while before unisonCloud is ready — although they have set up a new public-benefit company, Unison Computing, with funding, to help build this future.

In summary, we are currently building microservices that are way too heavy. They even carry around their own operating system. The next generation of microservices (which we can start building today) will shed this OS, and their outer layers, to become much smaller and way more focused. They’ll be pure (without side effects) and therefore easily testable, plugging directly into a much more intelligent platform — one that can traverse heterogeneous infrastructure and networks, easily spanning the globe. These microservices will be much easier and cheaper to build and operate.

But it’s not stopping there. Unison, or something similar, promises to allow individual functions to be scheduled literally anywhere, on a global execution substrate — virtual platforms that do not make a distinction between what we, today, call the cloud and the edge.

We can already do this to a certain extent with modern Content Delivery Networks (like Cloudflare and Fastly), but wasmcloud (and after that unisonCloud) blurs the distinction even further, creating truly infrastructure agnostic, intelligent platforms that span today’s cloud and edge/on-premise data centers.